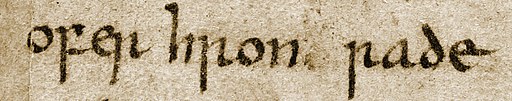

am looking at a puzzle framed in old oak, a parchment where Old English words pantomimed by Beowulf morph into Middle English and then into Shakespeare’s tongue, with Iago ready to do ill and Lear eager to blow his brains out.

am looking at a puzzle framed in old oak, a parchment where Old English words pantomimed by Beowulf morph into Middle English and then into Shakespeare’s tongue, with Iago ready to do ill and Lear eager to blow his brains out.

In this dangerous demilitarized zone, there is a clash of vowels and consonants. Elongated S’s, that could be perched on a music chart high in the throat, clash with architectural F’s that suggest, only at the northern tip, that I should form a sound by placing my front teeth on the outside of my bottom lip, less than a centimeter in distance, leaving little room for error.

Into this solipsistic and discordant jam session comes the eerie, high-pitched voice of a woman just short of being operatic, waltzing through the sounds of slowly moving turbines that are imagining steam, a medieval windmill that lifts buckets of water into a hungry arc, and then a low grade sputtering, as if her weighty entreaties have fallen in deaf ears.

Now she is forced to rely on her hands, as if she is standing in front of a Simon Says concert, rounding her fingers into bulls-eye where her fantasy chorus gets hold and cold, borrowing from another game, mere expressions away.

Out of breath, hands and spirit, the woman settles into the comfortable frame of a Maaco commercial, where a mechanic with perfectly coiffed hair and a Harvard accent says under her superlatives, “We get that a lot.”

Meanwhile, a black Labrador has been moaning at a high pitch throughout the proceedings and gives every indication he has understood all her throaty incantations. He slips to the floor, puts his hands over his ears, and sighs, as if reading the mechanic’s mind.

This tableau, delivered in the dream, is reward for spending the last week reading an 800-page 16th-century text about the Council of Trent (the place now part of Italy but then an implicit part of the German empire) that took place from 1545 to 1563 and pretty much governed the Catholic Church well into the 19th and 20th centuries. Paolo Sarpi’s “Istoria del Concilio Tridentino,” or History of the Council, was immediately put on the Church Index of banned books. I read a 1620 translation published in England. (This is part of a larger media project my brother and I are working on.)

The Council was supposed to be an answer to the Protestant Reformation and was encouraged by the rulers of France and Germany in particular where Lutherans were growing in restless numbers. I saw little of that, though the heavy, trenchant translated prose could have dulled my senses. What struck me most was how medieval many of the theological arguments were. On many occasions it was as if I was listening to a convention of astrologers and phrenologists, rather than the fabled scholastics I had met in school. And the money! It was instructive to learn to what extent money and monetary considerations fueled these theological proceedings that seemed to play out like Jacobean dramas.

When I hear the current Vatican Men’s Club, excluding Pope Francis, talk about the feminization of the priesthood, the cultural causes behind the sex crimes of priests and women who get plastic surgery, I hear some of the same tone-deaf male voices Sarpi brought to life in “Istorio” where the conversations they were engaged in seemed very far removed from The Sermon on the Mount. Current Cardinal Raymond Burke has been widely quoted about the “Man-crisis” in the Church. We would be grateful if he gave women the same consideration.

At the Council of Trent, there was little mention of women except for some language about arranged and secret marriages and why it was just to keep ex-concubines from joining a nunnery. Even though there were powerful female voices coming out of the Protestant Reformation that demanded the Church patriarchy recognize the essential equality of women in the eyes of God, the Catholic Church has remained inflexible on this point.

The Church was very late in addressing the feminine into its theological formulations, choosing to elevate the Virgin Mary through the Immaculate Conception and the Assumption in the 19th and 20th centuries, doctrines eventually weighed down by the Church’s teachings on sexuality and birth control. The notion of Papal Infallibility, not taken too seriously by the current Pope Francis, has been a source of friction in the church for hundreds of years, because it has as much to do with power and prerogative as doctrine per se.

The woman wailing in the Maaco repair shop is looking for the right language to state her concerns. The dream is about my demons and what I see projected on a muddled canvas that is sometimes called religion. I’m talking about soul work rather than body work.

And that’s what keeps me up at night.