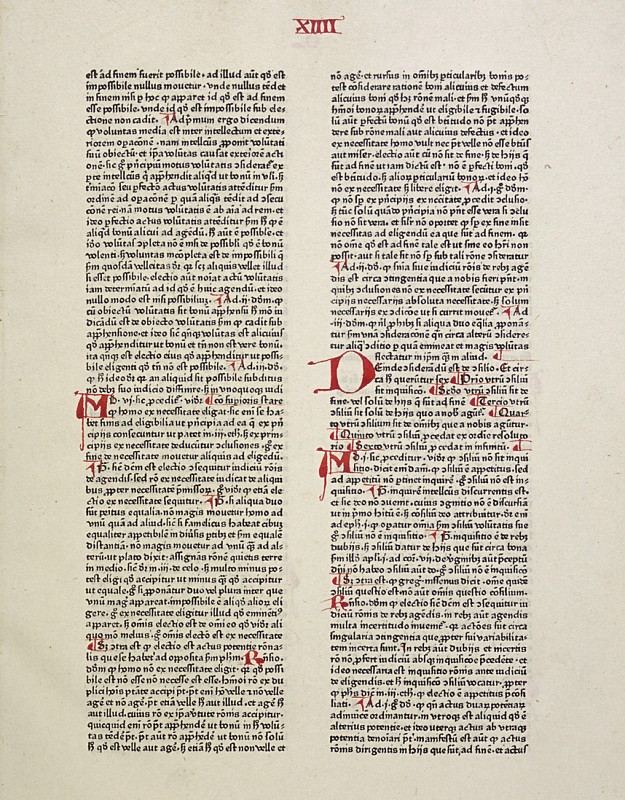

wenty-years ago, my son gave me a copy of “Pagans and Christians” for Christmas. The book’s essential premise was that the Catholic Church, given its power, reach, and longevity, has to be taken seriously, no matter one’s religious stripes. Or, in the words of the poet, “We grow by being defeated daily by increasingly powerful angels.” This daily defeat nicely described by the poet is particularly pertinent when one has the audacity to write about theology. In the spirit of the season and with an ache for a little light reading, I spent some days reviewing the various Catholic Church Synods or Councils where doctrine, theology, and creeds were discussed and decided upon. That my holiday study romp covered two thousand years provides fair warning that I am out of my element and swimming in very deep water. I was assisted by a number of books, with “The General Councils” by Christopher M. Bellitto the most readable. It is quite understandable that the early Christians struggled with issues related to the humanity and divinity of Jesus. That was the central issue at the Council of Nicaea (325) in present-day Turkey. The gathering faced a babble of tongues as the east spoke Greek and the west spoke Latin. Moreover, each language struggled to describe a mystery; a Christ who was fully human and fully divine in one nature. Theological splits were already evident at this early date. Because these issues were still hanging fire, another council was called in Constantinople (381) and Ephesus, Turkey (481), to discuss the Trinity and the Incarnation and Mary’s relationship to the godhead. As late as the seventh century, church fathers were still complaining about “serpents” in their midst spreading error throughout the body of the church. This language sounds remarkably similar to the current old Vatican guard who complain about Pope Francis’ “liberal” policies. Vatican intrigue is a very old story. By the ninth century much of church doctrine had been codified in the Apostles’ and Nicene Creed that laid out the above “mysteries” in black and white. At Nicaea II, in 787, the attendees addressed other contentious issues, including the veneration of icons, such as Jesus, Mary, and the Saints. Those in favor of this veneration claimed these icons provided a helpful intercession. Others who were opposed saw a veneration of false gods. The veneration camp won this round, but it was an issue that would come up again, especially during the Protestant Reformation. In the view of psychologist James Hillman, the Council’s support of representational art was not only a way to position their critics as heretics but also the first of many efforts by the church to control the imaginal lives of the devout. From a psychological perspective, this represented an effort to control the image-making potential of Christians and their private visions that could lead to false gods. Soul-making was to be the province of the priests. In his “Re-visioning Psychology” Hillman writes that the Council declared that “the composition of religious imagery is not left to the initiative of artists, but is formed upon principles laid down by the Catholic Church and by religious traditions. Painters were to be technicians following instructions from Church officials.” This method remained in principle and in general for centuries. The Church seemed to have a little to say over the years about women and the feminine principle. In the various councils, it did suggest that monks and nuns should not sing together in the same pew and nuns should not live in the same houses as priests. During the Middle Ages, parishioners were told to avoid attending mass offered by priests who lived with women. There were similar strictures for nuns. The Church wrestled with marriage between close relatives and generally prohibited marriages between anyone closer than a second cousin. It is curious that the church waited nineteen centuries before enshrining in doctrine both the Immaculate Conception (1854) and the Assumption (1950). There certainly seemed a compelling psychological need to honor Mary, though these doctrines have not done much to feminize the institution. The psychology of the church remains impeccably paternal. The effort to ban personalized images and a general image phobia, heightened during the Protestant Reformation and by Cromwell’s wrecking crew, can be found in Catholic, Jewish and Muslim traditions. But as the Catholic Church found out, the feminine principle will out. Hillman quotes an art historian to that effect. “We tend to take it for granted rather than to ask questions about this extraordinary predominantly feminine population which greets us from the porches of cathedrals, crowds around our pubic monuments, marks our coins and our banknotes, and turns up in our cartoons and our posters; these females variously attired, of course, came to life on the medieval stage; they greeted the Prince on his entry into a city, they were invoked in innumerable speeches, they quarreled or embraced in endless epics where they struggled for the soul of the hero or set the action going …” When I was studying theology in college, an instructor suggested that if Catholics took the time to read and understand the two thousand years of church history, they would leave the religion in droves. He was joking after offering a perspective on how church doctrine is so interwoven with politics, power plays, money, criminality, veniality and the like. He was equally attentive to divine inspiration but imagined a religion less heavy on theology and one more grounded in faith and good works. While writing this, I listened to a program on NPR about Pope Francis. A listener called in and said Francis sounds like the conversation “she tries to have at her local church.” This is the same man I hear in the Francis Twitter feed. I laughed when reading about Pope Francis’ admonishing of the Vatican staff in his Christmas message for their terrorism of gossip. I can imagine a pontiff admonishing a similar group at the Council of Trent, in northern Italy in 1545! During the NPR show, the host raised a question about American nuns who had been called on the carpet by the Vatican early this year for putting the needs of the poor, especially women and children, above doctrine. The Jesuit on the

wenty-years ago, my son gave me a copy of “Pagans and Christians” for Christmas. The book’s essential premise was that the Catholic Church, given its power, reach, and longevity, has to be taken seriously, no matter one’s religious stripes. Or, in the words of the poet, “We grow by being defeated daily by increasingly powerful angels.” This daily defeat nicely described by the poet is particularly pertinent when one has the audacity to write about theology. In the spirit of the season and with an ache for a little light reading, I spent some days reviewing the various Catholic Church Synods or Councils where doctrine, theology, and creeds were discussed and decided upon. That my holiday study romp covered two thousand years provides fair warning that I am out of my element and swimming in very deep water. I was assisted by a number of books, with “The General Councils” by Christopher M. Bellitto the most readable. It is quite understandable that the early Christians struggled with issues related to the humanity and divinity of Jesus. That was the central issue at the Council of Nicaea (325) in present-day Turkey. The gathering faced a babble of tongues as the east spoke Greek and the west spoke Latin. Moreover, each language struggled to describe a mystery; a Christ who was fully human and fully divine in one nature. Theological splits were already evident at this early date. Because these issues were still hanging fire, another council was called in Constantinople (381) and Ephesus, Turkey (481), to discuss the Trinity and the Incarnation and Mary’s relationship to the godhead. As late as the seventh century, church fathers were still complaining about “serpents” in their midst spreading error throughout the body of the church. This language sounds remarkably similar to the current old Vatican guard who complain about Pope Francis’ “liberal” policies. Vatican intrigue is a very old story. By the ninth century much of church doctrine had been codified in the Apostles’ and Nicene Creed that laid out the above “mysteries” in black and white. At Nicaea II, in 787, the attendees addressed other contentious issues, including the veneration of icons, such as Jesus, Mary, and the Saints. Those in favor of this veneration claimed these icons provided a helpful intercession. Others who were opposed saw a veneration of false gods. The veneration camp won this round, but it was an issue that would come up again, especially during the Protestant Reformation. In the view of psychologist James Hillman, the Council’s support of representational art was not only a way to position their critics as heretics but also the first of many efforts by the church to control the imaginal lives of the devout. From a psychological perspective, this represented an effort to control the image-making potential of Christians and their private visions that could lead to false gods. Soul-making was to be the province of the priests. In his “Re-visioning Psychology” Hillman writes that the Council declared that “the composition of religious imagery is not left to the initiative of artists, but is formed upon principles laid down by the Catholic Church and by religious traditions. Painters were to be technicians following instructions from Church officials.” This method remained in principle and in general for centuries. The Church seemed to have a little to say over the years about women and the feminine principle. In the various councils, it did suggest that monks and nuns should not sing together in the same pew and nuns should not live in the same houses as priests. During the Middle Ages, parishioners were told to avoid attending mass offered by priests who lived with women. There were similar strictures for nuns. The Church wrestled with marriage between close relatives and generally prohibited marriages between anyone closer than a second cousin. It is curious that the church waited nineteen centuries before enshrining in doctrine both the Immaculate Conception (1854) and the Assumption (1950). There certainly seemed a compelling psychological need to honor Mary, though these doctrines have not done much to feminize the institution. The psychology of the church remains impeccably paternal. The effort to ban personalized images and a general image phobia, heightened during the Protestant Reformation and by Cromwell’s wrecking crew, can be found in Catholic, Jewish and Muslim traditions. But as the Catholic Church found out, the feminine principle will out. Hillman quotes an art historian to that effect. “We tend to take it for granted rather than to ask questions about this extraordinary predominantly feminine population which greets us from the porches of cathedrals, crowds around our pubic monuments, marks our coins and our banknotes, and turns up in our cartoons and our posters; these females variously attired, of course, came to life on the medieval stage; they greeted the Prince on his entry into a city, they were invoked in innumerable speeches, they quarreled or embraced in endless epics where they struggled for the soul of the hero or set the action going …” When I was studying theology in college, an instructor suggested that if Catholics took the time to read and understand the two thousand years of church history, they would leave the religion in droves. He was joking after offering a perspective on how church doctrine is so interwoven with politics, power plays, money, criminality, veniality and the like. He was equally attentive to divine inspiration but imagined a religion less heavy on theology and one more grounded in faith and good works. While writing this, I listened to a program on NPR about Pope Francis. A listener called in and said Francis sounds like the conversation “she tries to have at her local church.” This is the same man I hear in the Francis Twitter feed. I laughed when reading about Pope Francis’ admonishing of the Vatican staff in his Christmas message for their terrorism of gossip. I can imagine a pontiff admonishing a similar group at the Council of Trent, in northern Italy in 1545! During the NPR show, the host raised a question about American nuns who had been called on the carpet by the Vatican early this year for putting the needs of the poor, especially women and children, above doctrine. The Jesuit on the  radio program indicated the Vatican had backed off, knowing that this was a sensitive subject in the U.S. Propublica.org just ran a piece entitled “U.S. Bishops Take Aim at Sterilization.” The Vatican bans sterilization for birth control and considers the practice “intrinsically immoral,” similar to abortion. But the publication notes that “for years Genesys Health System, a Catholic medical center near Flint, Michigan, allowed doctors delivering babies there to tie the tubes of new mothers who want to ensure that they never get pregnant again.” Now that policy is being reversed, apparently due to pressure from U.S. bishops. Performing a tubal ligation after childbirth is long-established care, especially if the woman is having a caesarean. Sarah Ward Prager, an associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Washington Medical School, says subjecting a new mother to a second surgery carries unnecessary risk. “It is simply unethical to say, ‘I’m going to make you come back to a different hospital to have another surgery in six weeks because the bishop says I can’t tie your tubes right now.’” Genesys says it has “updated its policy on tubal ligations to comply with current Catholic thinking.” In the 5th edition of “Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services” in 2009, U.S. bishops cite familiar doctrines. Based on natural law, children are the supreme gift of marriage and parents should understand that their proper task is transmitting life. Married couples may limit the number of their children by natural means. Contraceptives are not permitted. Surrogate motherhood is not permitted. Direct sterilization of either man or woman, whether permanent or temporary, is not permitted in a Catholic healthcare system. ProPublica suggests the Genesys decision is a sign of things to come. The Michigan ACLU is already involved. This doctrine will come under increased scrutiny as health care mergers increase and the Affordable Care Act takes root. It seems mildly ironic that the U.S. Conference on Catholic Bishops has decided to resurrect this theology of the body after losing the battle on birth control and also largely on abortion and the begetting of children. Catholics no longer listen to the clergy on matters of sex, morals, and reproduction. ProPublica provides a photo of a June 2014 meeting of the Conference in New Orleans during which the bishops voted to tighten rules on partnerships between Catholic and non-Catholic health care providers. In the picture, I count about twenty old, mainly bald, white men. There is nothing wrong with that picture. It’s been pretty much the same since the Council of Nicaea in 325, just three centuries after the death of Christ. No matter what Pope Francis does in Rome, reproductive rights will likely be the theological battle ground for American bishops going forward.

radio program indicated the Vatican had backed off, knowing that this was a sensitive subject in the U.S. Propublica.org just ran a piece entitled “U.S. Bishops Take Aim at Sterilization.” The Vatican bans sterilization for birth control and considers the practice “intrinsically immoral,” similar to abortion. But the publication notes that “for years Genesys Health System, a Catholic medical center near Flint, Michigan, allowed doctors delivering babies there to tie the tubes of new mothers who want to ensure that they never get pregnant again.” Now that policy is being reversed, apparently due to pressure from U.S. bishops. Performing a tubal ligation after childbirth is long-established care, especially if the woman is having a caesarean. Sarah Ward Prager, an associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Washington Medical School, says subjecting a new mother to a second surgery carries unnecessary risk. “It is simply unethical to say, ‘I’m going to make you come back to a different hospital to have another surgery in six weeks because the bishop says I can’t tie your tubes right now.’” Genesys says it has “updated its policy on tubal ligations to comply with current Catholic thinking.” In the 5th edition of “Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services” in 2009, U.S. bishops cite familiar doctrines. Based on natural law, children are the supreme gift of marriage and parents should understand that their proper task is transmitting life. Married couples may limit the number of their children by natural means. Contraceptives are not permitted. Surrogate motherhood is not permitted. Direct sterilization of either man or woman, whether permanent or temporary, is not permitted in a Catholic healthcare system. ProPublica suggests the Genesys decision is a sign of things to come. The Michigan ACLU is already involved. This doctrine will come under increased scrutiny as health care mergers increase and the Affordable Care Act takes root. It seems mildly ironic that the U.S. Conference on Catholic Bishops has decided to resurrect this theology of the body after losing the battle on birth control and also largely on abortion and the begetting of children. Catholics no longer listen to the clergy on matters of sex, morals, and reproduction. ProPublica provides a photo of a June 2014 meeting of the Conference in New Orleans during which the bishops voted to tighten rules on partnerships between Catholic and non-Catholic health care providers. In the picture, I count about twenty old, mainly bald, white men. There is nothing wrong with that picture. It’s been pretty much the same since the Council of Nicaea in 325, just three centuries after the death of Christ. No matter what Pope Francis does in Rome, reproductive rights will likely be the theological battle ground for American bishops going forward.